There were in fact two new and large scale choral works that had been commissioned for performance as part of the celebrations surrounding the consecration of Coventry Cathedral 50 years ago this May. One lost out to pacify the outspoken passions of the other. This is just part of the story of two titan works that Michael Foster’s book brings to life.

Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem was to be preceded six days earlier by an eighty minute cantata by Sir Arthur Bliss then Master of the Queens Music. Bliss’ The Beatitudes was a cantata for soprano, tenor, chorus, organ and orchestra. Its composition was intended for the vast spaces of the Cathedral and contained a substantial part for the magnificent new Harrison Organ – both still amazing visual and aural features of the Cathedral.

Rehearsals for both major works were dogged with problems from the outset.

War Requiem was particularly problematic. The early joint rehearsals were taken by Meredith Davies, the first in Coventry’s Central Methodist Church with the chorus ‘spread all over the place upstairs and down and Meredith Davies valiantly trying to fuse them into one complete unit.’

Britten (sitting) with Peter Pears who sang at the premiere of War Requiem in Coventry Cathedral

Other joint rehearsals took place in the Sibree Hall, the Police Assembly Hall, King Henry VIII School

With two new, large-scale works to be learned, a chorus that collectively did not have a great deal of experience (or expertise), rehearsals became ‘traumatic’ and, as the performances came closer, ‘every night of the week’.

By the time Britten arrived to participate in the later joint rehearsals of War Requiem what he found was a ‘shambles’, re-enforcing his original anxieties about the use of an ad hoc, ‘amateur’ chorus. By 30 April 1962 (some four weeks before the first performance) Britten was in despair about the viability of the Coventry

Britten’s attitude to the chorus turned hostile as he ended the joint rehearsal in Coventry

Something had to change.

The casualty of this particular war was The Beatitudes. The premiere was due to take place in the Cathedral on the night of the Consecration, 25 May 1962, but because of Britten’s panic over War Requiem and the need for more rehearsal time, a late decision was made to move The Beatitudes to the cramped and acoustically dead surroundings of the Coventry Theatre.

Bliss was devastated and, to this day The Beatitudes has never been performed in Coventry Cathedral for which it was so lovingly created.

Musical commentators almost universally refer to The Beatitudes as inferior to War Requiem, insignificant by comparison, a lesser work.

Those who will be lucky enough to be part of the audience on 22nd September when for the fist time The Beatitudes will be performed in the place for which it was written and accompanied by the organ for which much of the music was intended – they will surely see that this is no lesser a work.

Coventry Cathedral will enjoy The Beatitudes for the first time – 50 years and 4 months late, but so much better than never.

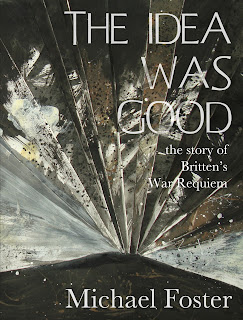

The new book - THE IDEA WAS GOOD - is now available for sale at £12.75 from Coventry Cathedral or on line at www.warrequiem.co.uk.

It tells the story of Coventry's phoenix-like growth after the war; of the Cathedral's commission as a beacon of hope and symbol of peace and reconciliation; and how War Requiem was written for and performed at its Consecration Festival in

May 1962.

Published by Coventry Cathedral with profits going to the Jubilee Fund.